Personal social networks and health: Conceptual and clinical implications of their reciprocal impact (2010)

Family Systems and Health, 28(1): 1-18

Author: Sluzki CE

< Return to ArticlesSluzki, CE (2010): “Personal social networks and health: Conceptual and clinical implications of their reciprocal impact.” Family Systems and Health, 28(1): 1-18

PERSONAL SOCIAL NETWORKS AND HEALTH: CONCEPTUAL AND CLINICAL IMPLICATIONS OF THEIR RECIPROCAL IMPACT

Carlos E. Sluzki

SUMMARY

Social networks impact positively or negatively a person’s health, and a persons’ health affects, in turn, their network’s availability. This article discusses this double dynamics, recommends the routine exploration of patient’s social networks, and offers a mapping tool that will allow to detect strengths and weaknesses of those processes, so as to facilitate interventions to improve the social support’s health-enhancing effect.

Every man is a piece of the continent, a part of the main.”

The field of Social Networks and Health, focused on the correlation between variables of our stable cocoon of relationships and health, has been expanding exponentially. A plethora of recent research provide evidence about the impact of those micro-social variables on health, healing and overall well-being. However, that field of inquiry, while conceptually a neighbor of ours, has been scarcely visited by those inhabiting the world of family systems and health. As a consequence, we may be missing the opportunity to enrich our field with many theoretical as well as practical corollaries derived from that literature. This articles aims at developing a bridge between these fields.

To begin with, it may be useful to challenge again, as family systems has done since its birth, a dominant notion in the professional literature of North American-European origin, namely, that our self is skin-bound, that our identity is a rock-solid personal possession.

Indeed, some experiences tend to reinforce that belief: we spend a week alone in a cabin in the mountains, or in a solo sailing experience, or we can even end up marooned, as Robinson Crusoe did for years, into a deserted island, and there we are, still recognizing ourselves as a unit … until the eyes of the other make their blessed reconfirming appearance in the person of another human being, the Friday of Crusoe, or, in the case of the main character of the film “Castaway”, by Wilson, a volley ball turned imaginary friend. And when we are wounded, it is us who are in pain…until the caress of another being to sooth us.

Our life is social from the moment we are born. In fact, newborns and young babies are extremely sensitive to the quality of their social context: they thrive with the reasonable quotient of stimulation, contingent responses, variety, acceptance, and tender affection by their parents and, parents helpers (grandparents, older siblings, etc.) or parent substitutes (caretakers in orphanages, baby-sitters, and the like) (Bowlby, 1969; Clarke-Stewart, 1977), or, if insufficient, their development can be delayed (Korner, 1974) and may regress, or even end in terminal marasmus (Bowlby, 1969.) Regardless of age, the “others” are a central feature of our life: Our identity, our self, our history, our memories live in a social milieu, embedded in a complex “spiral of reciprocal perspectives” (Laing, Philipson & Lee, 1966). Those who surround us are, ultimately, part of our-selves. This article will be devoted to this collective component of our identity.

OUR PERSONAL SOCIAL NETWORK

Our personal social network is a stable but evolving relational fabric constituted by our family members, friends and friendly acquaintances, work and study connections, and relations resulting from our participation in formal and informal communal organizations, including religious, social, recreational, political, vocational, health-related, and the like. Our social network includes, in fact, all those with whom we interact and who distinguish us (and, reciprocally, we distinguish) from the faceless, anonymous crowd. This social cocoon accompanies us, in an evolving form, from cradle to tomb, and constitutes a key repository of our identity and our history, and is a key ingredient of our sense of satisfaction and fulfillment with life. Kahn & Antonucci (1980) have coined the rich metaphor of a “social convoy” to refer to that interpersonal collective with reciprocal ties that travel with us through our (and their own) life-span, morphing as time passes and circumstances intervene in terms of membership, types of interaction, composition, and rules of reciprocity, adding ships while others sink over time, as ultimately we ourselves do in the Sargasso Sea of death.

The term “social network” has been applied to a variety of interactive social forms, from the connectedness that takes place as part of an internet system to the one that ties together sports or hobbies aficionados, from religious organizations that tie members through common rites and praying practices to the web that connected the 9/11 terrorists before their coordinated attack. A social network can be drawn as a bird’s eye view collection of nodes (dots) representing each member of an organization, or a neighborhood, or any specific population, plus ties (lines) that connect those nodes indicating a link or relationship, configuring a graph of one shape or another. In those cases, the centrality of one given node is circumstantial, in the sense that nodes/people that are very popular or powerful will have more ties connecting them with others than people who are new in to system or less powerful or more misogynous, while they can be visually located at any given area in the surface of the map.

That is not the case with the informant in the Personal Social Network, as discussed in this article. Rather than being designed as an ad hoc graph, it can be visualized as a constellation surrounding an individual, as it is an informant-based social network or ego-centric network (Fisher, 2005) that specifies the universe of social connections of a given person. Mapping such a network will assume that the individual whose personal social network is being elicited is at its center (mapping issues will be discussed in detail in a section below.)

Needless to say, the nuclear family constitutes the central component of that network during the first years of life. It expands, however, quite substantially the moment the child establishes relationships with other members of the community (children in playgrounds or in the neighborhood, students and teachers from kindergarten on), and further expands when the youngster becomes autonomous and establishes his or her own sphere of activity, be it a job or an advanced education, organizes his or her own family, and so on. That doesn’t necessarily vanish the role or impact of the family, but generates much more complex and diversified network of resources, which is the focus of this article.

The characteristics of a given individual’s personal social network vary from person to person, given different individual relational styles as well as many contextual variables. Extroverted people, i.e., people with propensity to connect with others [Totterdell, Holman and Hukin, 2008], have, not surprisingly, a richer social network than their counterpart, introverted people1. But people who have just moved into a new area will unavoidably have a skimpier and less varied social network than people well established in their community (Sluzki, 1992). And people suffering a chronic, limiting disease will experience a progressive decline of their social network, as will be discussed more in detail later in this article.

Personal social networks, both in their internal configuration and in their way of differentiating from a larger collective, vary from culture to culture, as cultures strongly influence the architecture of intimacy and responsibilities, the boundaries defining who is a member of a family and who is not, whom to be loyal to and whom to mistrust, as well as prescriptions and proscriptions of gender relations and rules of access to alternative support networks. Within each given cultural and socio-economic niche there will be a normative profile of individuals’ social networks, with its own predictable life cycle, in harmony with the life cycle of others members and vicissitudes of members of the nuclear family and its context. Needless to say, for each socio-cultural collective the “norm” is but an average of what in real life is a Gaussian curve that ranges from an extremely rich, varied and engaged network to extremely meager, scarce and distant one2. The latter will be highlighted here because they tend to impact negatively the health and well being of the individual.

The transition from a family-centered life to a predominantly socially centered reliance that followed the industrial revolution has been slow and extremely uneven worldwide. It has required relinquishing many old practices and learning new ones, some of which are at odds with what has been the long lasting cultural norm of a given family, clan, culture or region (Falicov, 2000; McGoldrick, Giordano & Garcia Preto, 2005,) shifting many social functions that were central for the development of people’s identity, sense of agency, and wellbeing from the family to community resources – school, day care center, the neighborhood, for instance.

Solid evidence of the impact of socio-economic and working variables on health has been drawn since that period. In fact, they constituted the basis for the development of much progressive labor and sanitary legislation over time. However, the first hard evidence singling out social relations as an independent variable affecting health can be credited to a study that opened the doors of empirical sociology, namely, Durkheim’s (1897) research that established a positive correlation between social isolation (anomy) and probability of suicide.

RESEARCH IN THE PAST 40 YEARS

During the past 40 years, scores of epidemiological studies as well as more focal investigations highlighted the impact of the personal social network, social integration, social support, social conflict or social capital3 on individual’s health.

During the early period of research on the subject, the question about the directionality of the process (Does a meager social network reduces psychological or physical resilience in individuals, o is it that a supportive social network function as a buffer against disease or death, or is it perhaps that the presence of an illness affects negatively the social network, reducing its availability?) was difficult to answer due to the retrospective design of that research. Namely, the research evidence had as point of departure a sample of problem subjects (such as people recovering from a heart attack, or a registry of recent suicides, and a control sample of healthy subjects) and therefore evaluated their social network at that point in time. Although allowing to establish differences between network traits of both samples, this approach did not inform whether the characteristics of the social network preceded (and eventually contributed to) the disease, or vice versa, or whether possible correlations between social network and in health/disease were both dependent on a third, still unspecified, variable.

This situation changed when a new generation of prospective research contributed robust evidence of the effect of social networks on health. This trend was preluded by Stanley Cobb (1976) and launched by the pioneer work of Lisa Berkmann and her team (Berkman, 1984; Berkman and Syme, 1979), who carried out a nine-year follow-up study of survival within a stratified random sample of 7000 adults. Once age, gender and prior health status were controlled, variables related to social connectedness4 emerged as a salient trait that differentiated those who had died during that interval and a matched sample of survivors.

To be precise, the adjusted relative risk of mortality of those in the lower end of their Social Network Index was 2.3 for men and 1.8 for women, i.e., men with a meager social network were more than twice likely to die and women almost twice as likely to die within those 9 years when compared with subjects with a more robust social network. This correlation between social network and health was maintained when those samples were re-analyzed controlling baseline health status (as informed by the subjects), socio-economic status (based on income and education), cigarette smoking, excessive weight, alcohol abuse, and level of physical activities.5

A confounding factor that the design of this project could not tackle was that their health data was obtained on the basis of a survey and a questionnaire, rather than clinically and, critics argued, people could have under-reported ill health and/or perhaps a lingering disease had negative effects on those individuals’ social networks before they themselves detected their illness6. However, a series of subsequent research projects launched at community health centers where a full health evaluation was conducted at the beginning of the study (House, Robbins, & Mekner, 1982, Schoenbach et al., 1986), and the subjects followed up no less than 9 years confirmed the results of the original study: individuals with an insufficient social network showed a statistically meaningful higher chance of dying earlier that people with a more robust social network.

Since then, demographic and social network variables have been correlated with health and well-being not only in the population at large but also in different specific sectors, including, in a necessarily incomplete list, a focus on:

- Children (e.g., Harkness and Super, 1994; Super and Small, 2002)7

- Old age (e.g., Adams & Blieszner, 1995; Bowling & Farquhar, 1991; Choi and Wodarski, 1996; Glass et al., 1997; Oman & Reed, 1998; Pilsuk & Minkler, 1980; Sluzki, 2000)

- Socioeconomic sectors, from the poor to the wealthy (Rosengren, Orth-Gomer and Wilhemsen,1998; Weyers, Drago, Mobus et al., 2008)

- Social network, social integration or social connectedness and morbidity and mortality (Berkman and Syme, 1979; Berkman, 1984; Berkman et al., 2004; Bosworth and Schaie, 1997; Hanson et al. 1989; House, Robbins and Metzner, 1982; House, Landis & Umberson 1988; Orth-Gomer and Johnson 1987; Ringback Weitoft, Haglund & Rosen, 2000; Schoenbach et al., 1986)

- Quality of life in different contexts (e.g., Adams & Blieszner, 1995; Kouzis and Eaton, 1998; Michael et al., 2001 and 2002; incidence of dementia (Fratiglioni et al., 2000), accidents (Tilman and Hobbs, 1949), relapses from schizophrenia (Dozeir, Harris and Bergman, 1987), stroke (Glass et al., 2000), coronary hearth disease ( Orth-Gomer, Rosengreen & Wilhemsen, 1993; Reed et al., 1983; Sundquist et al, 2004), problematic recovery from a heart attack (Medalie et al, 1973), physical and emotional symptoms following stressful events such as losing a job (Gore 1973), and even susceptibility to the common cold (Cohen et al. 2000, Pressman et al, 2005)8

In fact, this massive evidence has contributed to the development of a new discipline, named by two key researchers to that field as “Social Epidemiology” (Berkman and Kawachi, 2000.) This literature in turn enriches the new impetus in the field of public health that developed under the heading of “social determinants of health” (Willkinson & Marmot, 2003; Social and Economic Determinants of Health, 2007; CSDH, 2008; Healthy People 2010, 2009)

It should be noted that, while those studies were taking place – led mainly by epidemiologists, sociologists, and social psychiatrists and psychologists – the field of family therapy generated some interesting contribution of its own, focused on therapeutic perspectives targeting social networks of people in crisis. Among them can be mentioned Speck and Attenave (1973), Rueveni (1979), Trimble9, Landau (cf., e.g., Landau, Mittal & Wieling, 2008) and the author of the current article (Sluzki, 1985; 1992; 1993; 1995; 1996; 1998; 2000), as well as several books that highlighted a contextualized view of families, such as Schwartzman (1985) and Imber-Black (1988). The more recent literature on narrative, in turn, asserts that stories that organize realities “live” in the interpersonal space, that is, they are built and sustained (or changed) in conversation (of which White and Epston, 1990 was a pioneer.) Family therapy can be therefore described as the practice that through which stories that sustain problems, conflicts or symptoms by patients and families are collectively transformed into liberating stories that do not contain the conflict or the symptom. Many practitioners include in their sessions not only families but different “meaningful others” such as patient’s friends and colleagues. That is also the case when “interventions” are developed for addicted or alcoholic individuals.

SOCIAL NETWORK AND HEALTH

As this review highlights, there is ample evidence that a stable, sensitive, active and reliable personal social network has a salutogenic effect: individuals who count on a “good enough” personal social network show enhanced emotional resilience, and also display enhanced immunodefenses, getting sick less, and recover more readily from disease, surgery or accidents than those with a meager social network. A reliable social networks provides emotional support, sense of worth, reasons to remain alive when other reasons fail, and at the same time provides practical aid, act as referral agents, increases the appropriateness and timely utilization of health services, and nurse members into recovery. At the other end of the continuum, individuals with an inaccessible or meager social network show higher morbidity and mortality of a variety of diseases, as well as poorer recovery from them.

There is ample evidence to indicate that that correlation is both cause and consequence. Healthy people tend to accomplish emotional and practical support to other members of their network, and those actions in turn strengthen their network’s cohesion and potential responses to them when needed. But, while social networks tend to actively mobilize around members during their sickness and other crisis, prolonged chronic diseases, such as many cancers, schizophrenia, Alzheimer’s disease, progressive neurological conditions, et cetera, deteriorate in the long run the social offerings and social availability of their network.

In sum, the exploration of this evidence allows us to catch a glimpse at two antithetical recursive processes relating social networks and health:

- Virtuous (“salutogenic”) cycles, where the presence of a substantive social network protects and promotes the health of individuals and, reciprocally, the health of the individual contributes to maintain and enhance the network’s availability and responsiveness. It should be understood that “substantive” is not a mere reference to quantity, to number of people constituting the person’s network, but to the quality of the relationship, evaluated on the basis of intimacy, loyalty, availability, and equivalent attributes, which are discussed more in detail in subsequent sections of this article.

- Vicious (“pathogenic”) cycles, where a meager social network affects negatively the health of individuals, and diseases (specially lingering ones) in turn negatively impacts the resources and resilience of their social network, a decline that in turn negatively affects the health of the individuals, which in turn increases network attrition, in a spiral of reciprocal progressive deterioration or decay, not to mention the progressive overload for those who may remain involved.

SOCIAL NETWORK AND HEALTH: THEIR RECIPROCAL EFFECT

As clearly demonstrated by the contributions discussed above, the premise of a direct correlation between quality of the personal social network and health has been supported by ample evidence derived from empirical research, not to mention from clinical experience.

This correlation opens up several questions that merit being explored and, if possible, answered.

- Through which processes do solid, reliable and efficient personal social networks impact positively on the health of individuals? Stating it otherwise, how does participation in your social network gives you the best chances of maintaining and improving health? What constitutes a high quality social network or social community may be deconstructed in several overlapping processes:

- Social relations contribute to provide life meaning and role satisfaction to the participants, both as providers and as recipients of care, (“We love you, we need you!” AND “They need me; I am meaningful”) and motivate them to take care of themselves (Achat, Kawachi et al, 1988; Adams and Blieszner, 1995; Tobin & Neugarten, 1961)

-

A reliable PSN provides emotional support, which in turn mitigates alarm reactions, causally associated in the long run to disease (Achat et al. 1988; Blazer 1982), and facilitates coping and adaptation10. This “stress buffering hypothesis”, originally proposed by Cassel (1976) and Cobb (1976), tends to cover both emotional and instrumental resources. Several mechanisms have been proposed about the buffering effect. Among them may be mentioned that the assumption that others will be available when needed increases the individual’s ability to cope, as it leads the individual to perceive health crisis as less demanding (Adams & Blieszner, 1995; Cohen & Pressman, 2004; Thoits, 1986.) Also, the possibility (or at least the assumption of the possibility) to talk with others about stressful situations reduced both the emotional and the physical reactivity to those events, and potentially maladaptive behaviors (Lepore et al., 1996)

It should be also taken into consideration that the psycho-physiological reactivity to stressful events, while extremely varied among individuals, tends to be quite stable within individuals. And those who have a predictably stormy psycho-physiological reaction to stressful events, be it emotional or physical, are more susceptible to disease (Cohen & Hamrick, 2003). It merit being proposed that hyper-reactive individuals are more likely to exhaust their network with demands and expectations. But, alternatively, it could be suggested that those individuals broadcast their needs more openly and therefore elicit more responses within their surroundings, and they are responsive to the ministrations of their support network, thus generate a rewarding environment. - Reliable personal social networks provide practical/logistical support (“Go to hospital XX, they provide good care and speak our language. Bus N37 takes you there.”), dampening the experience of overload, resolving some problems, and activate and facilitate the access to health care resources (Cohen, Gottlieb & Undrewood, 2000a; Maitin, Weithington & Kesser, 1990.) For instance, Mexican American immigrants that live in areas with a high proportion of Hispanics enact better access to care than those who live in a culturally dissonant neighborhood (Derose, 2000; Roan Gresenz, Rogowski and Escarce, 2007), a finding that may be attributed to thicker social networking facilitated by shared language and customs among members of their “barrio.”

- Social relations provide feedback about signs of dis-ease and deviations from healthy practices (“You look too pale. Go see a doctor.”), triggering self or other health-caring behaviors (Cohen & Willis, 1985; Hajema, Knibbe & Drop, 1999)

- Life within a close-enough social network, such as family or other cooperative life arrangements, facilitates the maintenance of daily routines (such as regular nourishing meals, medications reminders) and provides normative (preventive) incentives (such as regular sleeping hygiene) which are associated to good health and appropriate self care (Baxter, Shetterly, Eby et al., 1998; Franssen & Knipsheer, 1990.)

- Through which processes does a scarce, unreliable or inefficient PSN have a deleterious effect on the health of individuals? This is, of course, a question that complements – or mirrors – the previous one.

- Social isolation forces an increase in overall alertness, a heightening of the “general adaptation syndrome” known to depress in the long run the psycho-neuro-inmunological system and, through that mechanism, increases susceptibility to disease;

- The scarcity of practical and logistic support reduces accessibility to health resources;

- The lack of a social “echo” – of being of value to others in one way or another – conspires against arguments that justify the effort to keep on living (Kouzis & Eaton, 1998);

- Through reduction of social monitoring and feedback (intrinsic to any situation of living in a collective), and even more with the added gray tinting of the world that characterizes depression, isolation generates carelessness, reducing the aversion for risk-taking behavior or at least muffling the appraisal process;

- Solitude reduces the incentives and social reinforcement for the maintenance of habits and routines associated to good health – from regular meals and sleep patterns to hygiene habits (Berkman and Syme, 1979);

- An unreliable or deteriorated social environments, such as that of an elderly person lacking family and friends and living in a poorly managed nursing facility or sequestered by his/her own family in a back room, the exposure to predominantly negative or infantilizing interactions (excessive demands or criticism, thoughtless or disrespectful behavior), erode the sense of purpose and of meaning in life, which in turn deteriorates physical and emotional health, as shown by Cohen, 2004, and, focusing on an elderly population, by Krause, 2004; Parquart, 2002, and Reker 1997

- By which process does the presence of a chronic and/or a severe illness of an individual have a negative effect on his/her social network, reducing the quality and quantity of the social offering and hence adding to the potential pathogenicity of disease?

- Any disease, especially if long lasting, debilitates and/or restricts the mobility of the individual him/herself, which in turn has an impact on behaviors of members of his/her network. This happens in two ways: Firstly, the lack of energy and motivation generated by a lingering disease, as well as the self-preoccupation of the diseased person and some frequent moderate level of depression, reduces the initiative of the individual to reach out and activate/maintain their existing network; and, as part of that process, and reduces the quality if not the quantity of acts of reciprocity (give and receive) in social exchanges, one of the motors that keep links alive (Plickert, Cote & Wellman, 2007; Vinokur and Vinokur-Kaplan, 1990.) Secondly, sick people are more homebound and/or have a more restricted motility, and that will reduce their opportunity for exposure to contexts in which social contact is available, thus contributing to their isolation (Feibel and Springer, 1982)

- The evidence of a disease of an individual has a predicable negative effect on others. This can be attributed to two reasons. One is that diseases have an aversive interpersonal effect in the non-immediate circle of relations. People instinctively tend to distance themselves from diseased individuals, reducing their availability, unless they belong to very intimate, close group, for whom the opposite is the case. There is some evidence also that the aversive effect is stronger when the sick person is male than when female, probably because in our society “the expression of distress is less role-appropriate for men, and therefore more likely to invite sanctions” (Johnson, 1991, p. 408.) The other reason is that the care of chronically ill individuals tends to be not rewarding (it is repetitive and with little perceived healing) and its lack of gratification reduces motivation for reiterated contact (Hamlett, Pellegrini & Katz, 1992; Pagel, Erdly & Becker, 1987), except in cultures with a strong family-oriented/duty bias, such as the Latino population (John, Resend & de Vargas, 1997.)

- Chronic disease has an attrition effect on caretakers. The care of chronically ill individuals tends to be resource-intensive, i.e., require time and effort, and hence debilitates the caretakers’ ability to care for themselves, socialize, and otherwise nourish their own needs11. Hence, caretakers end up also socially isolated, and their efficacy diminishes. Not surprisingly, the spouses of people with Alzheimer’s have been frequently labeled “the hidden victim” of that disorder.

However, chronic diseases may generate new networks for isolated individuals, as they may provide opportunity for contact with other patients also institutionalized, or with caretakers in the community. As an example, elderly people who live in their own dwelling but lack family and friends in their vicinity tend to maintain a thicker set of caretakers, be they physician, nurse practitioner, or rehabilitation specialists, as these professionals become an important source of self-affirming social contact and, in some cases, constitute the central characters in the patient’s meager social entourage.

MAPPING A PERSONAL SOCIAL NETWORK12

In a research endeavor, as well as in a practice, in the emergency room, in the rehabilitation hospital, in the nursing home, in the hospice shelter, and in the office, the PSN of a given patient can be evaluated and mapped in a short period of time, providing a useful summary of social network strength and shortfalls that merits being discussed in detail.

To start with, health professionals/caregivers will find revealing to explore the composition and accessibility of the patient’s social network in the course of a consultation, and make a note of areas of potential deficit.

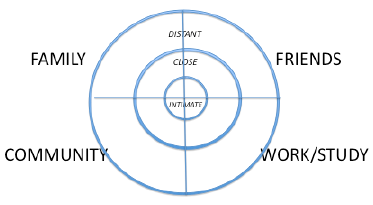

Information about a person’s social network tends to be easily accessible: people usually talk about their social world comfortably and without sense of being exposed. And patient or provider can be easily transcribe this information by into a map, as it does not require more equipment than pencil and paper nor an extended training by the interviewer. Figure 1 provides a blueprint for such a PSN map13.

The PSN map differentiates three layers of intimacy, designed as concentric circles around a central point, the informant: (I) a central circle encompassing an area corresponding to the intimate connections, people “close to our heart” with whom we can share intimacy, and/or rely upon without questions; this territory is generally occupied by close parents or siblings, a mate, close friends, and a few other special individuals, perhaps a trusted therapist or member of the clergy14, sometimes a co-worker or a school friend with whom we have total trust and confidence even while maintaining the relationship confined to the work-space; (II) an intermediate circle, encompassing an area of relations characterized by social connectedness without high degree of intimacy, including social friends (with whom we may share social activities such as dinners, sports, comfortable work or study exchanges, et cetera.); and (III) an external circle that delimits an area of acquaintances, that is, people with whom we have occasional contact, such as family members whom we meet in weddings and funerals, friends-of-friends with whom we interact circumstantially, the clerk of the corner store or our habitual hairdresser, with whom we exchange greetings and occasional courtesies, co-workers whom we greet in corridors, fellow students whom we know and who know us from shared classes and occasional exchanges, cult brethren, our internist’s stable receptionist, and so on. It establishes the boundary with the vast area of “the unknown other,” the millions of people whom we don’t know and who don’t know us. The test of membership in this territory, as opposed to that of “the others”, may lie in the answer to the question: “If you cross path with that person in a vacation spot, would you stop and greet and chat with them briefly?15”

The mapping of the PSN is further systemized by dividing it in four quadrants, namely (i) family, that is, those related to the informant by blood or by other family ties; (ii) friends and acquaintances, i.e., links that are based on personal empathy, those connected only by social ties; (iii) work and/or study relations that is, links established and maintained fundamentally within the confines of trade, profession or school joint activities; and (iv) community-based relations, including people with whom we know and know us on the basis of sharing membership in organizations, such as religious groups16, clubs, affinity groups and other outlets, including health and mental health, social or legal services, and the like17.

FIGURE 1: Diagram for mapping a personal social network: The four quadrants and three circles (reduced in size to 1/3 of the one used in practice)

This schematic design for a mapping should be understood as a toolbox to portray the composition, distribution and specific traits of a constellation of relations that constitutes an individual’s PSN. It has the merit of simplicity and practicality, perhaps its main claim when compared with other valuable social network tools and questionnaires, such as the Family Environment Scale [Moos and Moos, 1976], the Social Network Inventory [Berkman & Syme, 1979], or the Social Network Index [Cohen &Willis 1985]18. In fact, most of the parameters discussed here have been used, isolated or in combination, as independent variables in many of those tools.

The “inhabitants” of the social network can be elicited by a variation of the question “With whom have you had any interaction whatsoever in this past week that is not a total stranger, people whom you know as much as they know you? They may be even persons who don’t know your name or you theirs but know you.”

From that first set of questions, additional ones may flow, among which “Whom do you maintain contact with that are really important for you, and how frequently?”; “Who initiates the contact?”; “Whom do you trust implicitly?”; “Who is reliable and responsive to requests for help?”; “Whom do you go out with occasionally, in social activities?”; “Give me a list of all the persons in your current life that are close to your hearth” and so on.

In a first stage of mapping, each person will be marked in the map as a dot. Names, or number from a prior list of people generated by the informant, are written by each dot, for identification purposes (even pets, if mentioned by the informant, may be included in the “friends” sector.) In order to estimate centrality as well as density, in a second stage, lines are drawn between people/points in the map who know each other independently of the informant, such as friends of the informant who are friends between themselves. In a third stage, people who share household (family members, friends or acquaintances that may live with the informant, if any) and other specific clusters may be circled together. If the informant has migrated, marks about people living in different regions may be drawn with different colors, or circled.

As mentioned above, the portrait elicited by this inquiry is, in principle, static rather than dynamic, that is, at one point in time rather than over time. However, additional variations may include (a) exploring the evolution of the network at different points in time, such as eliciting a map responding to the question “If you would have drawn this map 3 years ago, what would have been different?” and comparing it with the one centered in the present; this becomes particularly relevant in sequential maps from the same informant two years before and after an event such as a marriage or a divorce, or the onset of a chronic disease; (b) including meaningful deceased people in it; (d) comparing dominant maps in samples of individuals belonging to specific cohorts, such as different social class, education, socio-cultural background, specific affinities, sexual orientations, disorders, etcetera.

It is possible, and in some case advisable, to conjointly map the shared and not shared social networks of couples, families, or other small groups. However, a joint map risks missing unevenness or major differences in terms of the individual contribution to the joint map. For instance, the information provided by the joint mapping of a couple’s network might contrast, sometimes dramatically, from the individual map of each members of the couple. Such as the case when one of them moved away from his or her prior neighborhood, town or country to live with the other, or one of them working in a socially rich environment and the other at home, or, as mentioned above, one may be simply more sociable than the other and therefore have substantive different individual personal network. These individual differences are a source of major conflict for some couples while, for others, they may operate as complementary traits that balance their social life for their mutual benefit.

For purposes of expanding the analytic capacity of this tool, a personal social network may be further evaluated according to structural, functional and trait variables19.

PSN’s structural characteristics include

- Size, i.e., number of members or “inhabitants”, total and by social quadrant

- Composition, i.e., distribution within and between the four social quadrants and the three circles or layers of intimacy

- Density, i.e., connectedness between members, independently of the informant, within and across quadrants (“Who among these knows whom, independently of you?”

- Dispersion, i.e., geographic or practical distance from the informant

- Degrees of homogeneity/heterogeneity, i.e., similarity or dissimilarity among members according to variables such as age, gender, cultural background, social class, ideology, perceived status, et cetera20; and

- Overall dominance of specific emotional and social functions and of link traits provided by the network (see next items)

Dominant emotional/social functions that each given relationship or social link accomplishes for the informant (these functions may overlap):

- Emotional support, i.e., “being there” for the other when needed, providing and/or receiving reliable empathic support and succoring [“Who is there for you in case you need somebody to hold your hand (or for you to hold their hand when they need it?)”]

- Social companionship, i.e., sharing pleasurable social activities such as going to the movies together, dancing, having dinner, shopping or hunting or praying together (overlapping with the prior one should not be assumed) (“Whom of these would do choose when you want to have a light social outing, dinner, the movies, or things like that?”):

- Cognitive guide & advice, i.e., providing or receiving practical advice, counseling, guidance at different junctures

- Social regulation, i.e., enforcing social does and don’ts by counsel, action or mere presence

- Material support and services, i.e., actual physical help as well as doing things for the other when needed; and

- Connection with other links/nets, not infrequently the role of more peripheral members, who may be more central in other networks (Granovetter, 1983) (“Who has been a good ‘bridge’ to open up new connections, when needed?”)

Last but not the least, the specific characteristics of the relationship between the informant and any given person in his or her network, that is, specific link traits, can be analyzed according to

- Actual frequency of contact

- Intensity, that is, commitment to the relationship

- Duration, that is, since how long they know each other

- Shared history, that is, how many memories do they share, and of what nature

- Emotional/social functions (already discussed above) that predominate in the relationship

- (Multi) dimensionality, that is, how many social functions characterize the relationship; and

- Reciprocity, i.e., ratio of “give and receive” transactions21.

These three sets of variables probably exceed the needs of a practicing clinician, and may risk overwhelming what may otherwise be a useful optic. They are specified here to highlight the richness of this perspective, and to open avenues for the research-oriented reader.

CLINICAL IMPLICATIONS

From the information obtained through the exploration of the social network of patients may derive important therapeutic implications.

Some of them will entail convening whomever is available in the person’s social network and conducting a collective session where problems are made explicit, risks are detailed, and plans are developed for a more effective management of the crisis or problem, along the lines of the “interventions” done with families with alcoholics, or the “network therapy” promoted by Speck and Attneave (1973). Others will activate a minimal component of the network, frequently family members, but maintaining a focus on the support of the extended resources. Finally, some interventions can only rely on the patient him/herself for the evaluation and interventions aimed at promoting supporting social connections22. The latter will require gently confronting some prejudices that permeate our culture, such as the assumption that to initiate a request for contacts imply weakness (i.e., that relationships should be maintained from a position of strength or at least reciprocity) and even less ask for help, or that the only way to measure others’ allegiance is to expect for them to initiate the contact (“They KNOW that I am feeble, or alone, so THEY should be the ones to contact me, not me to contact them!”). In those circumstances I may suggest that they call “just to chat”, without making any effort at transforming it into a visit. In fact, a task that I have favored is to make one phone-call per day to a person they have not seen in over two weeks, “just to chat,” which usually has a rather important activating effect in the network, as “the others” not infrequently feel either that they do not want to intrude, or that the contact is not valued by the individual, or even that they were not welcome.

Enacted in a psycho-educational mode, a primer on personal network enhancement may also include stimulating seeking, and providing, emotional support, as well as practical /logistic support with existing members of their network; developing comfort in providing, and accepting, feedback about deviations from health-enhancing practices; an insistence in the retention of routines – we, providers, are not only part of the patient’s network, but sometimes on of the few inhabitants of that social space; promoting and enhancing opportunities for exposures to contexts where social contacts are available – social, cultural, political, religious activities are all spaces where social connections can be established or reactivated… after some awkward first moments of self doubts and fears of rejection; enhancing reciprocity behaviors – such as calling to express appreciation for a visit, returning calls, answering letters, e-letters, and text-messages aimed at retaining relations; promoting social activities and recommend conversations that are not disease-based; enhancing support for caretakers of chronically ill or elderly infirm individuals; and one way or another, facilitating the development of new networks for patients as well as for caretakers. These observations apply in a very special way to the vicissitudes of recently migrated families (Sluzki, 1979.)

Another social dimension may be added to the above. One of the predictable effect of major catastrophes, both so-called natural (earthquakes, tsunamis, floods, hurricanes, and the sort) or manmade (collective violence and wars in any of its many variations), is the dismemberment of the social support network through social dislocation and forced migration when not due to death or disappearance of many meaningful members of the personal net, and the extinction of collective rituals that maintained people connected. Interventions aimed at reconnecting the remnants of the social network has been part of the focus of interventions of international reconstruction agencies as well as nongovernmental organizations, not only for purposes of the reestablishment of nuclei of civil society but because of its effect on enhancing resilience and improving survival (Barudy, 1989; de Jong 2002; Miller & Rasco, 2004; Landau, Mittal, & Wieling 2008.)

SOCIAL NETWORK ENHANCEMENT: A PRIMARY PREVENTION VIEW

The evidence of the impact of different qualities of the personal social networks on the health of individuals is overwhelming and conclusive: insufficient or inefficient social support associates positively with increased probability of getting sick, of remaining sick, of recovering more slowly, of increased complications during recovery, and, as a result, with experiencing a reduced quality of life and, alas, dying earlier. Stating it in a reversed fashion, a reliable and efficient personal social network will not only have a buffering effects against disease of every kind, resulting in a longer life, but will have a positive effect in the quality of the longer life lived.

However, there has been less emphasis in the reciprocal effect between those variables, namely, that the presence of disease, especially of chronic one, has a negative effect on the personal social network’s availability and efficiency, creating a potentially vicious cycle in which the insufficient or ineffective personal social network negatively affects health and disease negatively impacts on the social network. Both this negative cycle, and the complementary positive cycle between good health and an efficient social network, merit being incorporated into the optics of health care.

The analysis of these reciprocal processes not only enriches our understanding about the complex reciprocal influence between social surrounding and health but allows to propose additional avenues toward iimproving health, enhancing recovery, and living a longer, happier life.

More importantly, social network interventions constitute a powerful tool at the service not only when a disorder is already in place, integrated in a treatment plan, but for primary prevention. As the model of “advanced primary care” is moving front stage, the “medical home” principles of patient care coordination and sensitivity to the patients’ context must include in its optic not only the nuclear family but also the whole micro-cosmos of the extended personal social network. This mediating structure between the individual and the community at large not only reflects the community, but is in fact its immediate incarnation.

The exploration of patients’ personal social networks, including family members, friends, work or study connections, and community-based contacts, may lead to interventions that can play a crucial role in their immediate as well as long-range health recovery and maintenance, and in their overall well being. Interestingly, these very interventions may be also vital not only for those who consult us, but for the members of their social network, individually and collectively reaffirmed in their social and emotional value for one another.

REFERENCES

Achat, H.; Kawachi, I.; Levine, S; Berkey, C.; and Colditz, G. (1988). Social Network, stress and quality of life. Quality of Life Research, 7:735-50.

Adams, R.G. & Blieszner, R. (1995). Aging well with friends and family. American Behavioral Scientist, 39(2): 109-124.

Arling, G. (1976). "The Elderly Widow and Her Family, Neighbors, and Friends." Journal of Marriage and the Family, 28(4):757-768.

Barudy, J..A (1989). A programme of mental health for political refugees: Dealing with the invisible pain of political exile. Social Science & Medicine, 28(7): 715-727.

Baxter, J., Shetterly, S. M., Eby, C., Mason, L., Cortese, C..F, & Hamman, R. F. (1998). Social network factors associated with perceived quality of life. Journal of Aging and Health, 10(3), 287-310.

Berkmann, L.F. (1984). “Assessing the physical effects of social networks and social support”. Annual Review of Public Health, 5, pp.413-432.

Berkmann, L.F. and Syme L. (1979). “Social networks, host resistance, and mortality: A nine-year follow-up study of Alameda County residents.” American Journal of Epidemiology, 109(2), pp.186-204.

Berkmann, L.F. & Kawachi, I., Eds. (2000). Social Epidemiology. New York, Oxford University Press.

Berkman, L.F., Melchior, M., Chastang, J.F., Niedhammer, I., Leclerc, A. & Goldberg, M.(2004). Social integration and mortality: A prospective study of French employees of Electricity of France-Gas of France: The GAZEL Cohort. American Journal of Epidemiology, 159:167-174.

Blazer , D.G. (1982). Social support and mortality in an elderly community population. American Journal of Epidemiology. 115(5): 684-694.

Bosworth, H..B & Schaie, K.W. (1997). The relationship of social environment, social networks, and health outcomes in the Seattle longitudinal study: Two analytical approaches. Journal of Gerontology: Psychological Sciences, 52B(5): 197-205.

Bowlby, J. (1969). Attachment and Loss. Vol. 1: Attachment. London, Hogarth Press, and Institute of Psycho-Analysis.

Bowling, A., & Farquhar, M. (1991): Associations with social networks, social support, health status and psychiatric morbidity in three samples of elderly people. Social Psychiatry and Psychiatric Epidemiology, 26, 115-126

Capra, F (1997): The Web of Life: A New Scientific Understanding of Living Systems. New York, Anchor.

Cassel J. (1976). The contribution of the social environment to host resistance. American Journal of Epidemiology, 104, 107-123.

Choi, N.H. & Wodarski, J.S. (1996). The relationship between social support and health status of elderly people: Does social support slow down physical and functional deterioration? Social Work Research, 20(1): 52-63.

Clarke-Stewart, K. A. (1977). Childcare in the family: A review of research and some propositions for policy. New York: Academic Press.

Clifton, A. Turkheimer, E., & Oltmanns, T. F. (2009). Personality disorder in social networks: Network position as a marker of interpersonal dysfunction. Social Networks, 31, 26-32.

Cobb, S. (1976). Social support as a moderator of life stress. Psychosomatic Medicine, 38, 300-314.

Cohen, S. (2004). Social relationships and health. American Psychologist, 59(8): 676-684 (Special Issue: Awards Issue 2004).

Cohen, S., Brissette, I., Skoner, D.P. & Doyle, W.J. (2000a), Social integration and health: The case of the common cold. Journal of Social Structure 1(3):1-7

Cohen, S,, Gottlieb, L. & Uniderwood S, (Eds.). (2000b). Social Support Measurements and Interventions. New York: Oxford University Press

Cohen, S. & Hamrick, N. (2003): Stable individual differences in physiological response to stressors: Implications for stress-elicited changes in immune related health. Brain, behavior and immunity 17: 407-414.

Cohen, S. & Pressman, S. (2004). Stress-buffering hypothesis. In Anderson, N.B. (Ed.): Encyclopedia of Health and Behavior. Thousand Oaks, CA, Sage (p.780-82).

Cohen, S. & Willis, T.A. (1985): Stress, social support, and the buffering hypothesis. Psychological Bulletin, 98:310-357

CSDH (2008). Closing the gap in a generation: health equity through action on the social determinants of health. Final Report of the Commission on Social Determinants of Health. Geneva, World Health Organization.

De Jong, J.T.V.M. (2002). Public mental health, traumatic stress and human rights violations in low-income countries: A culturally appropriate model for times of conflict, disaster, and peace. Chapter in J.T.V.M. de Jong (Ed.): Trauma, War, and Volence: Public Mental Health in Socio-Cultural Context. New York, Kluwer/ Plenum (pp.1-93)

Derose, K.P. (2000). "Networks of Care: How Latina Immigrants Find Their Way to and Through a County Hospital", Journal of Immigrant Health, 2(2): 79-87.

Dozier, M., Harris, M. & Bergman, H.(1987). “Social network density and rehospitalization among young adult patients.” Hospital and Community Psychiatry, 38(1) pp.61-65.

Durkheim, E. (1897): Suicide. New York, Free Press, 1951

Falicov, C.J. (2000): Latino Families in Therapy: A Guide to Multicultural Practice. New York, Guilford.

Feibel, J. & Springer, C. (1982). Depression and failure to resume social activities after a stroke. Arch Phys Med Rehabil 63:276-278.

Fisher, D. (2005): Using egocentric networks to understand communication. IEEE Internet Computing 9(5): 20-28.

Franssen, M-J., & Knipscheer, K. (1990). Normative influences of the intimate social network on health behavior. In K. Knipscheer & T. C. Antonucci (Eds.), Social Network Research: Substantive Issues and Methodological Questions (pp. 17-29). Amsterdam: Swets & Zeitlinger.

Fratiglioni, L.; Wang, H.K., Ericsson, K., Maytan, M. & Winblad, B. (2000). Influence of social networks on occurrence of dementia: A community-based study. The Lancet, 355: 1315-1318.

Glass, T.A.; Mendes de Leon, C.F.; Seeman, T. & Berkman, L.F. (1997). Beyond single indicators of social networks: A LISREL analysis of social ties among the elderly. Social Science & Medicine, 44(10): 1503-1517

Glass TA, Dym B, Greenberg S, Rintell D, Roesch C, Berkman LF. (2000) Psychosocial intervention in stroke: the Families in Recovery from Stroke Trial (FIRST). Am J Orthopsychiatry, 70:169-81

Gore, S. (1978). The effect of social support in moderating the health consequences of unemployment. Journal of Health and Social Behavior. 19:157-165.

Granovetter, M. (1983). The strength of weak ties: A network theory revisited. Sociological Theory, 1:201-233.

Hajema, K.-J, Knibbe, R.A., & Drop, M.J. (1999). Social resources and alcohol-related losses as predictors of help seeking among male problem drinkers. Journal of Studies on Alcohol. 60, 120-129.

Hamlett, K.W.; Pellegrini, D.S. and Katz, K.S. (1992). Childhood chronic illness as a family stressor. Journal of Pediatric Psychology, 17(1): 33-47

Hanson, B.S., Isaacson, S.O., Janzon, L. & Lindell, S.E. (1989)., Social network and social support influence mortality in elderly men: The prospective population study of ‘Men born in 1914.’ American Journal of Epidemiology, 1989, 130(1): 100-111

Harkness, S. & Super, C.M. (1994). The developmental niche: A theoretical framework analyzing the household production of health. Social Science & Medicine, 38(2):217-226.

HEALTHY PEOPLE 2010; www.healthypeople.gov, or www.bcbsmnfoundation. org/pages-exploretheissues-tier4-Social_Determinants_of_Health_General_ ?oid=7784

House, J., Robbins, C. and Mekner, H. (1982). “The association of social relations with mortality: Prospective evidence from the Tecumseh Community Health Study.” American Journal of Epidemiology, 116, pp.123-140.

House, J.S., Landis, K. R., & Umberson, D. (1988). Social relationships and health. Science 29(July), 540-545.

Idler, E.L. and Benyamini, Y. (1997). Self-rated health and mortality: A review of twenty-seven community studies. Journal of Health and Social Behavior (38):21-37.

Imber-Black, E. (1988). Families and Larger Systems: A Family Therapist's Guide through the Labyrinth. New York, Guilford.

John, R., Resendiz, R., & de Vargas, L. W. (1997). Beyond familism?: Familism as explicit motive for eldercare among Mexican American caregivers. Journal of Cross-Cultural Gerontology, 12, 145-162.

Johnson, T.P. (1991). Mental health, social relations, and social selection: A longitudinal analysis. Journal of Health and Social Behavior, 32:408-423

Kahn, R. L., & Antonucci, T. C. (1980). “Convoys over the life course: Attachment roles and social support.” In P. B.Baltes & O. G. Brim (Eds.) Life-span development and behavior, New York: Academic Press (pp.253-286).

Klein Ikkink, K. and van Tilburg, T. (1999). Broken ties: reciprocity and other factors affecting the termination of older adults’ relationships. Social Networks, 21(131-146).

Korner, A. (1974): Individual differences at birth: Implications for child care practices. Chapter in Bergsma, D (Ed.): The Infant at Risk. New York: Intercontinental Medical Book.

Kouzis, A.C. & Eaton, W.W. (1998): Absence of social networks, social support and health services utilization. Psychological Medicine, 28,(6),1301-1310

Krause, N. (2004). Stressors in highly valued roles, meaning in life, and the physical health status of older adults. Journals of Gerontology, Series B: Psychological Sciences and Social Sciences, 59, S287-S297.

Kraut, A., Melamed, .S, Gofer, D. & Froom, P. (2004): Association of self-reported religiosity and mortality in industrial employees: the CPRDIS study. Social Science and Medicine, 58:595-602.

Landau, J., Mittal, M., & Wieling, E. (2008). Linking Human Systems: Strengthening individuals, families, and communities in the wake of mass trauma. Journal of Marriage and Family Therapy. 34(2): 193-209.

Lazarsfeld, P., and R. K. Merton. (1954). Friendship as a Social Process: A Substantive and Methodological Analysis. In M. Berger, T Abel, and C. H. Page, eds.: Freedom and Control in Modern Society,. New York: Van Nostrand (pp.18-66).

Laing R., Phillipson, E. & Lee, A.R. (1966). Interpersonal Perceptions: A Theory and a Method for Research. London, Tavistock.

Lepore, S.J., Silver, R.C., Wortman, C.B. & Wayment, H.A. (1996). Social constraints, intrusive thoughts and depressive symptoms among bereaved mothers. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 70, 271-282.

Maitlin, J.A, Weithington, E.M. & Kesser, R.C. (1990). Situational determinants of coping and coping effectiveness. Journal of Health and Social Behavior, 31:103-122

McPherson, M., L. Smith-Lovin, and J. Cook. (2001). Birds of a Feather: Homophily in Social Networks. Annual Review of Sociology. 27:415-44.

Medalie, J., Snyder, M. Groen, J.J., Neufeld, H.N., Goldbourt, U. & Riss, E. (1973). Angina pectoris among 10,000 men: 5-year incidence and unvaried analysis. American Journal of Medicine, 55:583-594.

McGoldrick, M.; Giordano, J.; Garcia-Preto, N, (Eds.) (2005). Ethnicity & Family Therapy.(Third Edition) New York, Guilford.

Michael, Y.L., Berkman, L.F., Colditz, G.A. & Kawachi I. (2001): Living arrangements, social integration, and change in functional health status. American Journal of Epidemiology, 153 (2): 121-131

Michael, Y.L., Berkman, L.F., Colditz, G.A. , Holmes, M.D. & Kawachi, I. (2002). Social networks and health-related quality of life in breast cancer survivors: A prospective study. Journal of Psychosomatic Research, 52(5):285-93.

Miller, K. E . & Rasco, L. M. ( Eds.) (2004). The Mental Health of Refugees: Ecological Approaches to Healing and Adaptation. Mahmah, NJ, LEA.

Moos, R.H. & Moss, B.S. (1976): Family Environment Scale. Palo Alto, Consulting Psychologists Press.

Oman, D. & Reed, D. (1998).. Religion and mortality among community-dwelling elderly. American Journal of Public Health, 88:1469-75.

Orth-Gomer, K. & Johnson, J.V. (1987). Social network interaction and mortality: A six year follow-up study of a random sample of the Swedish population. Journal of Chronic Disease, 1987, 40(1): 949-57.

Orth-Gomer, K., Rosengren, A. & Wilhelmsen, L. (1993), “Lack of support and incidence of coronary heart disease in middle-aged Swedish men”. Psychosomatic Medicine, 55, pp.37-43.

Pagel MD, Erdly WW & Becker J (1987): Social Networks: We get by with (and in spite of) a little help from our friends. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 53(4):793-804

Parquart, M. (2002). Creating and maintaining purpose in life in old age: A meta-analysis. Aging International, 27, 90-114.

Pilsuk, M. & Minkler, M. (1980). Supportive Networks: Life ties for the elderly, Journal of Social Issues, 36(2): 95-116.

Pilsuk M. and Hiller Parks, S. (1986). The Healing Web: Social Networks and Human Survival. Hanover, NH: University of New England Press.

Plickert, G., Cote, R.R., Wellman, B. (2007), It’s not who you know, it’s how you know them: Who exchanges what with whom? Social Networks, 29:405-429.

Pressman, S.D., Cohen, S., Miller, G.E., Barkin, A., Rabin, B.S. & Treanor, J.J. (2005). Loneliness, social network size, and immune response to influenza vaccination in college freshmen. Health Psychology 24(3):297-306.

Reed, D., McGee, D., Yano, K., & Feinleib, M. (1983): “Social network and coronary heart disease among Japanese men in Hawaii.” American Journal of Epidemiology, 117, pp.384-396.

Reker, G. T. (1997). Personal meaning, optimism, and choice: Existential predictors of depression in community and institutional elderly. The Gerontologist, 37, 709-716.

Ringback Weitoft, G., Haglund, B. & Rosen, M. (2000). Mortality among lone mothers in Sweden: A population study. The Lancet 355: 1214-1219

Roan Gresenz, C., Rogowski, J., Escarce, J.J. (2007). Social Networks and Access to Health Care Among Mexican-Americans. (US) National Bureau of Economic Research Working Paper No. 13460. Issued in October 2007.

Rueveni, U. (1979). Networking Families in Crisis. New York, Human Science Press.

Rogers, E.M. (2003). Diffusion of innovations (5th ed.). New York: Free Press.

Rosengren, A., Orth-Gomer, K., Wilhemsen, L. (1998). Socioeconomic differences in health indices, social networks and mortality among Swedish men. A study of men born in 1933. Scandinavian Journal of Social Medicine, 26(4): 272-280.

Schoenbach, V., Kaplan, B.H., Friedman, L., & Kleinbaum, D. (1986). “Social ties and mortality in Evans County, Georgia.” American Journal of Epidemiology, 123, pp.577-591

Schwartzman, J., Ed. (1985). Macro-Systemic Approaches to Family Therapy. New York: Guilford Press.

Sluzki, CE (1979): "Migration and Family Conflict”. Family Process, 1979, 18(4):379-390

Sluzki, CE (1992): "Disruption and reconstruction of networks following migration/ relocation." Family Systems Medicine, 10(4): 359-364.

Sluzki, CE: (1993) “The social network: Frontier of systemic therapy”. Therapie Familiale, Geneve, 14(3):239-251(In French)

Sluzki, CE (1995a) “De como la red social afecta a la salud delindividuo y la salud del individuo afecta a la red social.” In Dabas, E. & Najmanovich, D., (Eds.).. Redes Sociales: El Lenguaje de los Vinculos. (“Social Networks. The language of bonds.”)Buenos Aires, Paidos, pp.114-129.

Sluzki, CE: (1995b ) “Getting married and un-married: Vicissitudes of the social network during marriage and divorce”. Generations, 5:44-51, 1995 (in French)

Sluzki CE (1996): La Red Social: Frontera de la Practica Sistemica. Buenos Aires/Barcelona, Gedisa (in Spanish); and (in Portuguese) Sao Paulo: Casa do Psicologo, 1997

Sluzki, CE: (1998) “Migration and the disruption of the social network,” chapter in McGoldrick, M. ed.: Re-Visioning Family Therapy: Race, Culture and Gender in Clinical Practice . New York, Guilford Press.

Sluzki CE (2000): “Social Networks and the Elderly: Conceptual and Clinical Issues, and a Family Consultation.” Family Process, 39(3):271-284.

Social and Economic Determinants of Health, updated (2007). www.doh.wa.gov/HWS/doc/context/context-SOC2007.pdf

Speck, R. & Attneave, C. (1973). Family Networks. New York, Vintage.

Sundquist , K, Malmström, M. & Johansson, S-E. (2004): Neighbourhood deprivation and incidence of coronary heart disease: a multilevel study of 2.6 million women and men in Sweden J Epidemiol Community Health. 58:71-77

Super, C.M. & Small, S. (2002). Culture structures the environment for development. Human Development, 45:270-274.

Thoits, P.A. (1986). Social support as coping assistance. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, 54:416-123

Tillman, W. and G. Hobbes (1949). “The accident-prone automobile driver: A study of psychiatric and social background.” American Journal of Psychiatry, 106, pp. 321-30.

Tobin, S.S. and B. L. Neugarten (1961). "Life satisfaction and social interaction in the aging." Journal of Gerontology 16 (October): 344-346.

Totterdell, P., Holman, D. & Hukin A. (2008), Social networkers: measuring and examining individual differences in propensity to connect with others, Social Networks (30): 283-296

Vinokur, A.D. and Vinokur-Kaplan, D. (1990). In sickness and in health: Patterns of social support and undermining in older married couples. Journal of Aging and Health, 2(2):215-241.

Weyers, S., Drago, N., Mobus, S., Beck, E.M., Stang, A., Möhlenkamp, S., Jöckel, C.H., Erbel, R. and Siegrist, J. (2008). Low socio-economic position is associated with poor social networks and social support: results from the Heinz Nixdorf Recall Study. Int J Equity Health. (May) 7:13.

White, M. & Epston, D. (1990): Narrative Means for Therapeutic Ends. New York, W.W.Norton

Willkinson, R. & Marmot, M. ,Eds. (2003): Social determinants of health. The solid facts (Second Edition). Geneve, Switzerland, WHO Press.

ENDNOTES

- In the realm of psychopathology, people with a diagnosis of narcissistic and histrionic personality disorders show a richer social network, and frequently occupy a more central position in the personal social networks of others, than people with a diagnosis of avoidant, schizoid and schizotypal personality disorders (Clifton, Turkheimer and Oltmanns, 2009)

- While not specifically pertinent to the scope of this article, we cannot ignore that dramatic circumstances such as major uprooting and displacement both within countries (as is the case of the so called internally displaced persons) or between countries (as is the case of refugees) are the frequent result of natural or human-made catastrophes, that drastically dislocate whatever social network people may have, compounding the ordeals that this embattled segments of the civil population may have to endure.

- For a detail of those instruments, see http://trans.nih.gov/CEHP/HBPdemo-socialconnectmeasures.htm.

- In that study, “social connectedness” included marital status, contacts w/close friends and relatives, church membership, and membership in informal and formal group associations, analyzed separately as well as aggregated in a Social Network Index.

- As in any multivariate analysis, there were several trade-off substitutions that derive from this analysis: for instance, subjects that are not married but with many friends had similar mortality rates than married but with fewer friends.

- It was later shown that global self-rated health has shown to be by itself a solid independent predictor of mortality in longitudinal studies (cf. Idler and Benyamini, 1997.)

- These authors followed a more anthropological vein in their research, operationalizing in their studies the “developmental niche” as composed by three operational subsystems: “(1) the physical and social setting of the child’s everyday life; (2) the culturally regulated customs of child care and child rearing; and (3) the psychology of the caretakers.” (Harkness & Super 1994, p.217)

- For a broad strokes superb summary of the connection between social network and health variables, cf. also Capra,1997.

- David Trimble edited between 1986 and 1995 the “Netletter,” a low budget, information-rich, clinically oriented publication focused on social network interventions.

- For instance, for many elders, even with reduced motility and other foibles of age, this health-enhancing influence may be stronger with the continued involvement with friends and neighbors that with a well-intentioned move to an offspring household distant from their original dwelling, as the former entail continuity, shared history and life style, while the latter may increase dependency and a stressful adjustment to a new environment (Arling, 1976).

- It should be noted that all these considerations may apply also to the plight of the elderly, even when reasonably healthy, especially if socially isolated – while there is strong evidence that the availability of the informal support provided by the extended network of the elderly is more bound by the size of the network that by the specific demands for care (Choi and Wodarski, 1996).

- An early incursion into this theme by the author of this article appeared in Spanish in Sluzki (1995a).

- To trace the genealogy of this specific model and map is a rather difficult task, as, like so many other models, it contains traits by a multiple progeny, including but not limited to contributions by Pilsuk and Hiller Parks (1986) and so many others.

- Reciprocity, while a dimension of a relationship, is not a necessary condition for inclusion. Hence, for instance, a trusted therapist or a specific wise clergyperson of our congregation may be experienced by us as important potential resources and merit being included as part of the inner circle within our social network, while they may perceive themselves a resource for us, but not vice-versa, and they would not include us in their own social networks map. An extreme example to this is the attachment developed by many people to public figures, including politicians, actors and entertainers, who may occupy in important place in the public’s life even though no personal relation has been established with them, beyond the pne fostered by a sector of the press solely dedicated to sustain that interest through photos and gossips about these characters’ lives and tribulations, which affects those involved as if this information would be one related to family or close friends.

- Throught the text, some sample questions wil be included fas suggestion to explore specific issues. They will appear in italics.

- A more subjective, self-reported measure, namely “religiosity”, has shown an interesting age-related difference: in a 12-year follow-up study (Kraut et al, 2004), it associates with lower adjusted mortality for younger respondents and with higher adjusted mortality for a 55-year or older cohort, as compared with nonreligious respondents. In regard to religious collectives and health, see also Oman & Reed, 1998.

- These distant relations play, however, a crucial role: as their own personal social network generally does not overlap much with that of the informant, these relations open doors to other networks, allowing for contacts that otherwise would be accessible. Hence the felicitous description of Granovetter (1983) about “the strength of weak ties.”

- This tool, utilized by Cohen and his collaborators in many of their projects, can be found in http://www.psy.cmu.edu/~scohen/SNI.html

- Far from defining these variables as original, the author should make it clear that this listing borrows heavily from many authors, chiefly Berkman and Cohen (see several references for these authors,) reserving for himself only some systematization of them as well as any errors.

- This variable is affected by two opposite social tendencies: homophily, i.e., the tendency of individuals to associate with similar others (a notion introduced by Lazarsfeld and Merton, 1954; and extensively reviewed by McPherson, Smith-Lovin, and Cook, 2001); and heterophily, i.e., the tendency to connect with diverse groups (Roger 2003). The former facilitates reconfirmation of views and the latter fosters innovative ideas.

- Reciprocity of contacts, frequent interactions, proximity, shared history and shared activities keep alive a relation (Klein Ikkink & van Tilburg, 1999). Of course, reciprocity may me embedded in extended ledgers – such as the case of offspring caring for an ailing parent on the basis of an emotional need to reciprocate for the ministrations received in turn during the first decades of their life.

- A caveat: There are toxic relationships (relations that foster dependency or that consistently negatively label the patient) that people do better to avoid, unless couched toward a transformation of that relationship. Hence, the quality of the relationship is an important variable to consider. However, valuable-but-distanced relationship may be an important target for attempts at re-connection.